NGC 6578

Among the more obscure of brighter planetary nebulae, NGC 6578 is buried

deeply within the star clouds of northern Sagittarius somewhat under a degree north-northeast of

Mu Sagittarii. Far away (from a

combination of inaccurate methods perhaps 6500 light years) and

young, it is angularly small, just 8.5 seconds of arc in diameter,

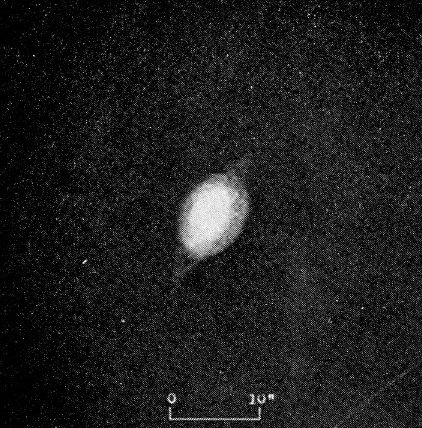

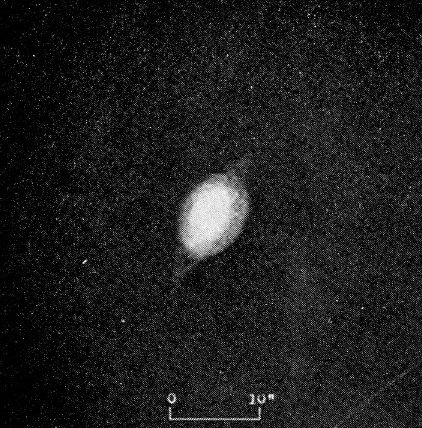

or about a quarter of a light year across. Curtis (left-hand

image) says little: "Disk nearly round...no ansae or structural

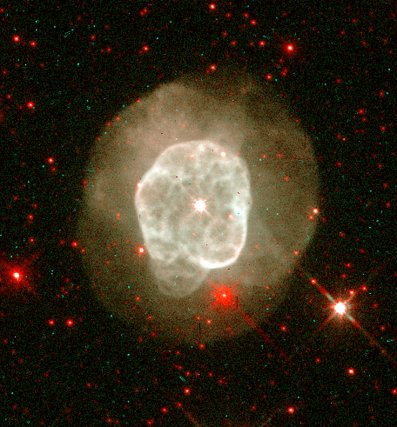

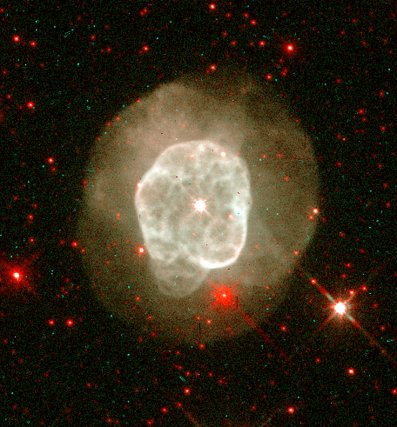

details visible...Rather faint." Hubble on the other hand (at

right) reveals a classic double shell, the inner one filled with

expanding threads of gas and caused by a fast wind from the central

star hammering the outer envelope. While Curtis could not see the

fainter outer halo, he was right, there are no ansae or jets as in

NGC 7009 or NGC

6543. What may seem to be jets in his drawing are (from the

Hubble image) clearly just extensions of the inner shell. Why some

nebulae have ansae and others do not is a mystery. Part of the

object's faintness is due to some three magnitudes of absorption of

light by intervening dust in the thick mid-line of the Milky Way, the nebula a mere 10 degrees from the

center of the Galaxy.

Curtis was close in his assessment of the central star, estimating

it at magnitude 15, which modern methods show to be 15.7.

Combination of nebular and stellar brightness gives a cool (for

such objects) temperature of 63,000 Kelvin (consistent with little

or no ionized helium

radiation) and, from the distance, a

luminosity of about 4000 times that of the Sun. Theory then indicates a core mass (that

of the old nuclear burning remnant of the original star) of 0.57

times that of the Sun, which in turn suggests an initial mass

(before the star lost its outer envelope) of around 1.3 times

that of the Sun, all this discussion very uncertain. Modest mass,

though, goes along with no evidence for chemical enrichment of the

nebula. The star is still in a state of heating with more or less

constant luminosity, and when it hits about 100,000 Kelvin, it will

begin to cool and dim, while the nebula, expanding at about 20

kilometers per second, will dissipate into space, leaving a modest

white dwarf

behind.

Left: Image by H. D. Curtis from Publications of the Lick

Observatory, Volume 13, Part III, 1918. Right: Hubble image by H.

Bond (STScI) and NASA.