NGC 6543

THE CAT'S EYE NEBULA

One of the brightest planetary

nebulae in the sky, NGC 6543 is of great historical

importance. The "first planetary," the one to which William

Herschel first applied the term, is the Saturn Nebula, NGC 7009 in Aquarius. But it was in the Cat's Eye, NGC 6543 in Draco, that he found the first known

central star. Herschel thought that he had discovered star birth, that the nebula was

condensing to form the star. While he had it backwards (the

nebula actually ejected by a dying star), his brilliance was in

that he understood that these objects had something to do with

stellar life cycles. The Cat's Eye was also the first planetary

nebula to have its spectrum examined, by

William Huggins in 1864. Listen to his words from his 1897

memoir, which reflect Herschel's ideas and reveal his thrill at

his great discovery:

"On the evening of August 29, 1864, I directed the

telescope...to a planetary nebula in Draco. The reader may be

able to picture to himself...the feeling of excited suspense,

mingled with a degree of awe, with which, after a few moments of

hesitation, I put my eye to the spectroscope. Was I not about to

look into a secret place of creation?

I looked into the spectroscope. No such spectrum as I expected!

A single bright line only! ...

The light of the nebula was monochromatic, and so, unlike any

other light I had yet subjected to prismatic examination, could

not be extended out to form a complete spectrum...A little closer

looking showed two other bright lines on the side towards the

blue. The riddle of the nebulae was solved. The answer, which

had come to us in the light itself, read: Not an aggregation of

stars, but a luminous gas" [emissions being characteristic of

hot gases under low pressure].

Huggins had discovered an emission line of hydrogen in the blue

part of the spectrum and two "mystery lines" in the green that

were later thought to come from an unknown element called

"nebulium." Among the strongest emissions in planetary nebulae,

the "nebulium" lines were finally found by I. S. Bowen in 1928 to

be emissions of doubly-ionized oxygen

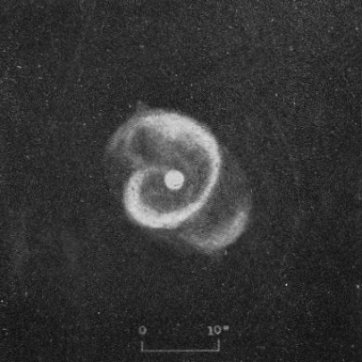

On the left is Curtis's drawing. Made from several photographic

images, gives a sense of the object's visual appearance through

the telescope. On the right is the Hubble Space Telescope's view,

which shows vastly greater detail with intricate interlocking

rings and a stunning bipolar flow quite like the ansae seen in NGC

7009. With a decently known distance of 3000 light years

(determined from the expansion of the nebula coupled with the

expansion velocity of around 20 kilometers per second), the main

body of the nebula is some 0.4 light years across, while the twin

flows stretch out to about twice that distance. (One source,

however, suggests 5000 light years from the same data, showing how

tricky distance measures really are.) Surrounding the Cat's Eye

is a huge shell from earlier stellar winds with a diameter of

close to 4.5 light years, somewhat larger than the distance from

the Sun to Alpha Centauri. Concentric rings reveal episodic mass

loss. The ionic excitation is relatively low, as there is no

ionized helium. With a temperature of about 50,000 Kelvin, the

11th magnitude central star is still heating with a total

luminosity of around 1000 times that of the Sun.

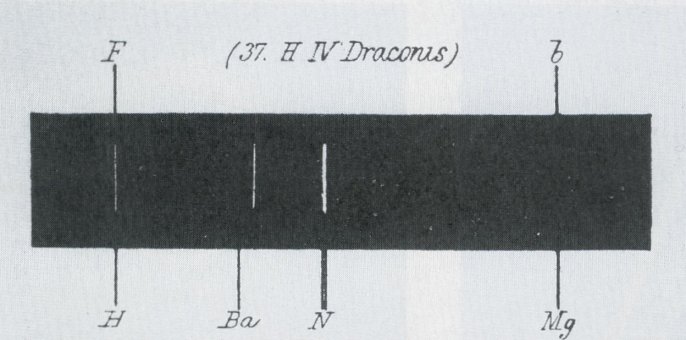

Above is the simple drawing of the spectrum of NGC 6543 as seen

through the visual spectroscope of Sir William

Huggins in 1864. It shows the two forbidden oxygen lines at 5007

and 4959 Angstroms just to the right of center and to the far left

the H-Beta line of hydrogen, tagged "H" at the bottom. The tag

"F" at the top of H-Beta is a Fraunhofer designation applied

before any celestial (specifically solar) spectrum lines were

identified. An expected magnesium line (Fraunhofer "b") does not

show up. The forbidden lines were not identified as doubly

ionized oxygen until 1928, and were at the time thought to be from

nitrogen (hence the tag "N" at the bottom). See them in the

spectra of NGC 7009 and NGC 2440. The observations of the

emission lines proved for the first time that planetary nebulae

were gaseous. A similar observation of the Orion Nebula followed in 1872, showing that diffuse

nebulae were gaseous as well.

Image at left by H. D. Curtis from Publications of the Lick

Observatory, Volume 13, Part III, 1918. Right: NASA, ESA,

HEIC, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA). Quote and spectrum from

The Scientific Papers of Sir William Huggins, London:

William Wesley and Sons, 1909.